What the heck is a Turky Carbuncle??

With my book finished, my collections delivered, and my office clean, I have returned to doing a bit of transcription. I am still working on the eternal Chapter IV from Shrines of British Saints , and as I’m typing along I come across this tasty little morsel:

By virtue of this commission [Henry VIII’s destruction of monastic shrines] there was taken out of the cathedral of Lincoln, on the 11th of June, 1540, 2,621 ounces of gold, and 4,285 ounces of silver, besides a great number of pearls and precious stones which were of great value, as diamonds, sapphires, rubies—

—

[Wait for it—]

turky carbuncles, etc.”

lol! Back to my first question, what the heck is a Turky Carbuncle?

I should mention this phrase seems all the funnier to me because the book’s author, especially in describing the greed and destruction of Henry VIII and his commissioners, at times sounds very indignant. So when a seemingly snooty and indignant person complains to you about the loss of his turky carbuncles…well, you could see that might elicit a giggle or two!

And the answer is:

Especially garnets, but any deep red stone with no faceting and a round shape was known in the middle ages as a carbuncle. (This is why the sore on your behind after a day on horseback is also called a carbuncle; it, too, is deeply red and round.) As to a ‘turky’ carbuncle, I couldn’t find anything in particular. But I am guessing it is a type of carbuncle associated with belonging to the Turkish territory or Muslim people.

And if you know something else about it, please let me know.

Though I can’t help thinking of all those gorgeous gold and garnet ornaments made during the dark ages by the Germanic barbarian goldsmiths. Were the garnets in those beautiful creations also called carbuncles? And if so, I think that’s a shame. Such extraordinary work, and the best compliment the poor artist could get was “Lovely work, Ulfic, love those pulchritudinous carbuncles.” Hm…not good.

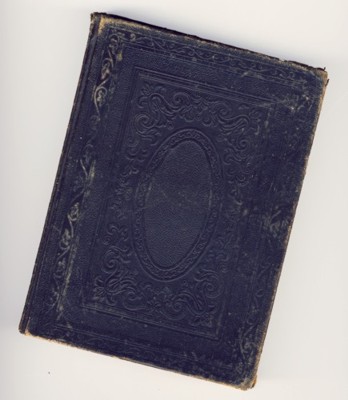

What’s a Gefangbuch you ask? It’s a German devotional book filled with prayers, psalms, devotional readings, and hymns.

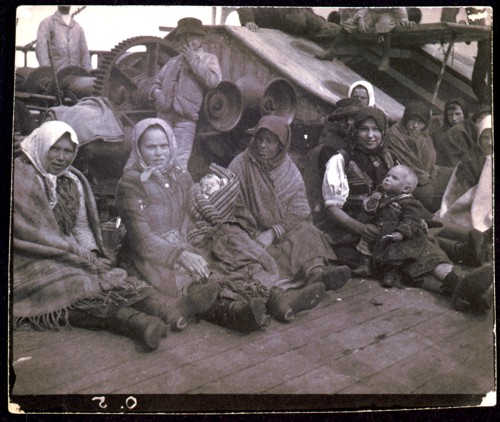

I found this wonderfully battered copy locally. There were many German immigrants to Oregon Territory and this book, published in 1884, might have crossed the Atlantic with an immigrant headed for work in Fishers Quarry for all we know. Perhaps the owner sailed round the horn. Or maybe boarded the transcontinental railroad and headed west.

It’s really hard for Americans now to imagine the hardships of the ocean immigrant journey. Many who took the trip had nothing, brought nothing. Maybe just a prayer book.

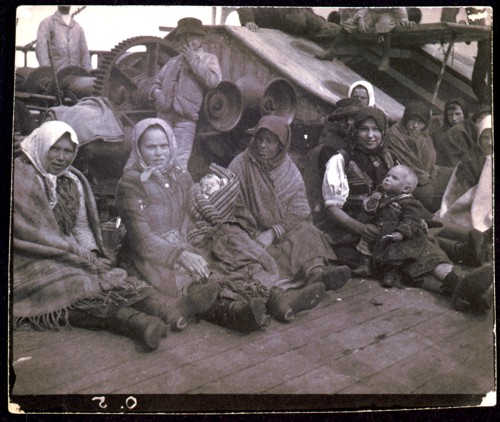

(photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston, c1899)

I came across the above picture while doing research on the web. The picture is from the Library of Congress’ online website, as are the two beneath it. We can’t imagine what it might have been like then. In America’s malls we are so insulated from poverty and desperation. But the fact is that this kind of ‘have nothing’ immigration still persists. But today immigrants travel to Europe, not away from it, and the immigrants are from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

Regardless of who and where and when, human beings all have a habit of fleeing the same things—persecution, poverty, hunger, crop failure, calamity, tragedy. And these scenes of flight were all strangely printed on stereograph cards to be viewed in the parlors of the newly mobile and industrial Americans. Perhaps because they symbolized hope for the future more than the desperation of the past.

(photo by William H. Rau, c1902)

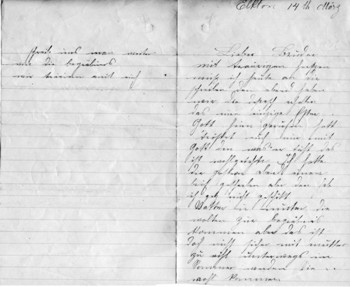

This next image, also from half an old stereograph card, shows a group of Italians coming to America. They were refugees fleeing the disaster of 1908, when a massive earthquake and tsunami left 100,000 of their countrymen dead.

(photo by B.W. Kilburn, c1909)

I am curious about the stories of those people. Some of the stone cutters who landed at Solomon Fisher’s Landing were Italians. There were Swedes and Austrians too, and of those immigrants who found work in Fishers quarry, some died fast, and young, before anyone even knew who they were or could contact their families. These quarrymen are buried at Fishers cemetery, though their wooden markers are long gone. We will never know their story.

But for some immigrants, proof exists. Like this hymn and prayer book, this Gefangbuch, which was perhaps the only thing small enough to carry and important enough to hang on to. This prayer book, which, from a letter tucked inside its pages, might yet offer up some part of its owner’s story to tell.

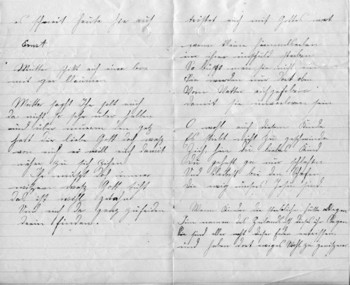

Can anyone translate the German?

(Yes! We have a translation. Our letter is a letter of condolence. See “update” below.)

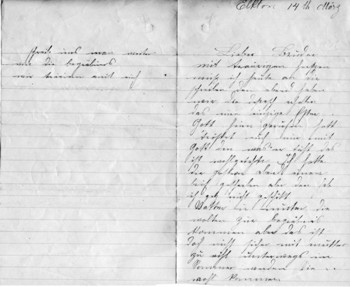

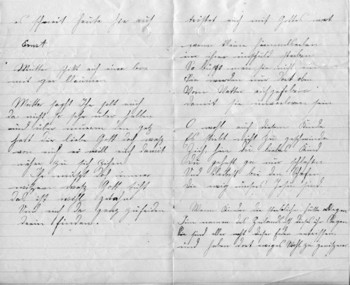

(Front and back pages. View larger image here .)

(Middle pages. View larger image here .)

I’d love to know who wrote this letter and what it says. I only know enough German to recognize the word Mutter (Mother). Yet this little bit of insight makes me assume that whoever it was who owned this book, they tucked this letter into their hymnal so they could carry with them news of home.

-Richenda

Update! August 4, 2008.

We have a translation for the letter, thanks to Leiselotte Kill, who translated it, and her sister-in-law Sharon who made that possible. Thank you!!

And I learned something I didn’t know before. This letter was tricky to translate in part because it is written in the “old Sütterlin” handwriting style, used primarily in Germany, though also by others, primarily before WWII, though it was also used in some places later than that.

As with other old letter styles, it can flummox those who are not used to them. This caused other nice folks who first looked at this for me (thank you!!!) to throw their hands up and scratch their heads in bemusement.

All the more wonderful to get a translation. Leiselotte was nice enough to include not just a Sutterlin to English translation, but a Sutterlin lettering to today’s German lettering translation, as well.

So, three translations below:

Straight transcription of the letter:

Lieber Bruder

mit traurigem Herzen muß ich heute an dir schreiben den abend haben wir die Depesch erhalten das eure einzige Ester Gott heimgerufen hatt tröstet euch nur mit Gott den was er tuht das ist wohlgetahn Ich hatte dir gestern abend einen Brief geschrieben aber den hab ich gez nicht geschikt Vatter u muter wolten zur Begräbnis kommen aber das ist doch nicht sicher mit mutter zu vihl unterwegs im Sommer werden Sie . . wohl kommen.

Schreib uns man weiter von die Begräbnis wir trauern mit euch

Translation of the old into today’s German (So müsste es wohl korrigiert heißen):

Lieber Bruder,

mit traurigem Herzen muss ich heute an dich schreiben. Am Abend haben wir die Depesche erhalten, dass Gott eure einzige Ester heimgerufen hatt. Tröstet euch nur mit Gott, denn was er tut, das ist wohlgetan. Ich hatte dir gestern Abend einen Brief geschrieben, aber den hab ich jetzt nicht abgeschickt. Vater u. Mutter wollten zum Begräbnis kommen, aber das ist doch nicht sicher mit Mutter. Zu viel unterwegs. Im Sommer werden sie wohl kommen.

Schreib uns von dem Begräbnis. Wir trauern mit euch.

Translation from today’s German to English (Versuch einer Übersetzung):

Dear brother,

With a sad heart I must write to you today. This evening we received the telegram saying that God has called your only Ester to Himself. Console yourselves with God, for what He does is well done. Last night I had written a letter to you, but I didn’t post ist. Father and mother wanted to come to the funeral, but now it’s not sure with mother yet. Too much being on the road (Alt. Too much travelling). Maybe they’ll come in summer (Alt. They will most likely come in summer).

Write (Alt. and tell us about) the funeral. We mourn with you.

Ask, and ye shall receive.

Curious about those sweaty monks from my previous blog?

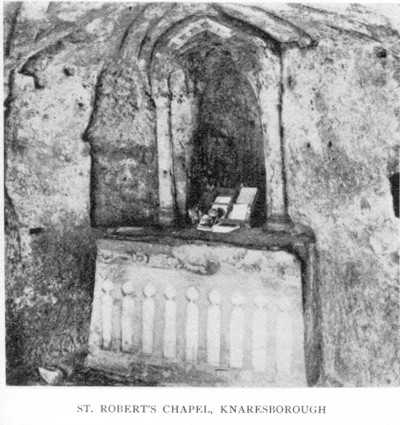

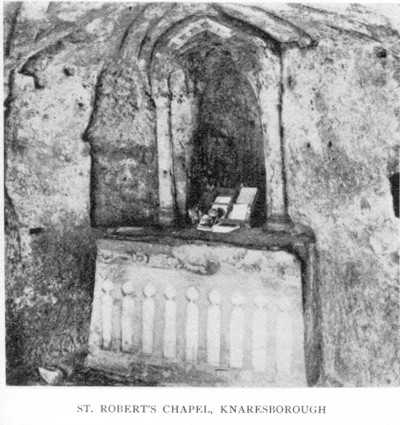

In a nutshell, St. Robert was a hermit and should probably be the patron saint of prisoners as that was a favorite ministry for him, taking in and redeeming, aiding, helping thieves and other prisoners. He seems to have fashioned a small monastic type hermitage in Knaresborough that included a cave dwelling, a chapel, a guest house, and a farm.

As to the group of monks called “Robertines,” I haven’t learned too much more about that. My guess is this Robert was a charismatic leader and holy man and of the “crowds” that came, a few chose to stay and follow him. Who these “Robertines” were I’m not sure, but probably officially consisted primarily of Brother Ive, who was Robert’s hermit companion. The “Robertines” became Trinitarians, as it was that group that took over the hermitage and chapel after Robert’s death.

Certainly the demise of Robert was treated like the demise of an Abbot, with the property reverting to the King (and benefactor) until a successor could be named.

Here’s the story of Robert of Knaresborough, excepted from Mary Rotha Clay’s The Hermits and Anchorites of England.

The story of Robert of Knarlesborough [Excepted pages 40-44]:

Robert of Knarlesborough was a citizen of York. According to a fourteenth-century chronicle, his surname was Koke. Leland calls him “one Robert Flowr, sunne to one Robert Flowr, that had beene 2 tymes Mair of York”. Other authorities give his father’s name as Touke or Tok Flour, and his mother’s as Onnuryte, Simunina, or Sunniva.1 The pious youth became a lay brother of Newminster in Northumberland, but after a few months he sought stricter seclusion. Being doubtless well acquainted with Knaresborough (only eighteen miles from his home), he determined to join a certain knight, rich and famous, who, having fled from the lion-like wrath of Richard I, was living apart from men on the banks of the Nidd. The two men dwelt together in a cave ; but, after the king’s death, the fugitive warrior returned to the world :—

Langir lyked hym noght that lyffe

Bott als a wreche wentt to hys wyffe,

leaving the “soldier of Christ” alone.

The young solitary was befriended by a virtuous matron named Helena, who gave him the chapel of St. Hilda at Rudfarlington in Knaresborough forest.2 There he abode for a while, but when thieves broke into his hermitage, he moved on to Spofforth. Then, fearing lest the crowds which followed him should move him to vainglory, he accepted the invitation of the monks of Holy Trinity, York, to join some of their number at Hedley. The young zealot, clad in an old white garment, who would eat nought but barley bread and vegetable broth, was not a comfortable companion, and Robert, regarding his fellows as “fals and fekyll,” returned to St. Hilda’s. The noble dame was passing glad to see him, and provided a barn and other buildings for his use. William de Stuteville, Constable of Knaresborough, passing by, saw the dwelling, and when he heard that one Robert, a devoted servant of God, lived there, he cried : “This is a hypocrite and a companion of thieves!” and bade his men “dyng doune hys byggynges”. The homeless hermit took his book and fared through the forest to Knaresborough :—

To a chapel of syntt Gyle

Byfor whare he had wouned a whyll

That bygged was in tha buskes with in

A lytell holett : he hyed hym in.

But again the lord of Knaresborough went a-hunting, and when he was smoke rising from the hut, he swore that he would turn out the tenant. That night there “appered thre men blacker than Ynd,” who roused him [William] from his restless sleep. Two of them harrowed his sides with burning pikes, whilst the third, of huge stature, brandished two iron maces at his bedside : “Take one of these weapons and defend thy neck, for the wrongs with which thou spitest the man of God”. William cried for mercy and promised to amend his deeds, whereupon the vision vanished. Early in the morning the terrified tyrant hastened to the cell, and humbly sought pardon :—

Roberd forgaff and William kissed

And blythely with hys hand hym blyssed.

The penitent baron then bestowed upon Robert all the land between the rock and Grimbald Kyrkstane, besides horses and cattle.

William de Stuteville was succeeded by Brian de Lisle, who regarded the hermit as his faithful friend. It was he who besought King John to visit Robert (see p. 153). This visit resulted in the further endowment of the cell. John bade Robert ask what he willed, but he relied that he had enough, and needed no earthy thing. When Ive found that alms for the poor hand not been asked, he persuaded his master to follow the king, from whom he receive the grant of a carucate of land. This land was appropriated to the use of the poor, and Robert refused to pay tithe for it to the rector, to whom he indignantly granted “crysts cursynge” for his covetousness.

Robert was “to pore men profytable”. He gathered alms for the needy, fed them at his door, and sheltered them in his cave. The complaint made by the angry baron that the hermit was a receiver of thieves had some truth in it. In the rhyming life, Robert speaks of the corn required for “my cayteyffes in my cave”. His favourite form of charity was to redeem men from prison :—

To begge an brynge pore men of baile

This was hys purose principale

St. Robert died on the 24, September, 1218.3 He had been a benefactor to many, and great was the grief of the mourners. As he had foretold on his death-bed, the monks of Fountains sought to bear away his body, but Ive carried out his master’s wish to be buried in the chapel of the Holy Cross, where he had himself prepared a rock-hewn grave.

I wyll be doluen whar so I deghe

Beried my body thare sall ytt be

Wyth outen end here wyll I rest

Here my wounyng chese I fyrste

Here wyll I leynd here wyll I ly

In this place perpetuely.

The chroniclers call St. Robert’s first hermitage “the chapel of St. Giles,” describing it as a dwelling under the rock formed by winding branches over stakes in front of a cave. They relate how his brother Walter, who was mayor of York, thought this cavern and wattled hut no fitting habitation for him, and suggested that he should join some community. Robert replied : “This is my resting-place for ever : here will I dwell, for I have chosen it”—an answer which recalls the antiphon sung when a recluse was about to enter his life-long retreat. Walter therefore sent workmen from the city who laid the foundations of a chapel in honour of the Holy Cross, built of hewn stone. Evidently this chapel adjoined the cave, and replaced the humble oratory of St. Giles. […]

After Robert’s death, the cell was claimed as Crown property. A writ was issued (1219) to the Constable of Knaresborough to cause “our hermitage” to be given into the custody of Master Alexander de Dorset. The original grant was afterwards confirmed to Brother Ive, hermit of Holy Cross (1227).4 The chapel became a place of pilgrimage, and many miracles of healing were wrought there, especially about twenty years after the saint’s death. “The same year (1238) shone forth the fame of St. Robert the hermit at Knaresborough, from whose tomb medicinal oil was brought forth abundantly.” Matthew Paris, naming in 1250 the chief personages of the last half-century, mentions in particular St. Edmund of Pontigny, St. Robert of Knaresborough, and St. Elizabeth of Hungary.5 The new priory (or “House of St. Robert”) was granted to the Trinitarian Friars, and it was fitting that the “Order of the Holy Trinity for the Redemption of Captives” should become successors of the saint two had delighted in releasing men from prison. The name Holy Cross or Holy Rood was superseded by that of the hermit. In 1257 Richard, Earl of Cornwall, confirmed to the Order the chapel of St. Robert.

About Robert the Farmer [Excerpted from page 101]:

Robert of Knaresborough was another hermit-husbandman. He fared frugally, but one day he was left hungry, for robbers invaded his dwelling and stole his bread and cheese. After a time he was granted as much land as he could dig, and later, as much as he could till with one plough. he was also given two horses, two oxen, and two cows. Robert’s parable was an ear of corn (p. 153) ; and the miracles ascribed to him are the miracles of a farmer. He tames the wild cow, and yokes to his plough the stags which trample his corn :—

Hertes full heghe of hede and horn

Vsed to come to Robertt corn. . .

He wentt and wagged att them a wand

And draffe thise dere hame wt hys hand.

This legend, and also that of a counterfeit cripple, who begged a cow from St. Robert, were depicted in a window set up in Knaresborough church in 1473.6

About Robert and Brother Ive [Excepted from page 129]:

Robert of Knaresborough was joined by Ive and by several servants, who shared his labours. The story of Ive seems to show that even in the “solitary” life, two were better than one, for the strong would lift up his fellow. One day Ive attempted to return to the world which he had renounced. In passing through the forest, however, he broke his leg with the bough of a tree, and fell into a ditch, where he sat “alas! alas! waloway!” Robert, supernaturally aware of what had happened, hastened thither, and not without mirth at his friend’s plight, pointed the moral : “No man, having put his hand to the plough and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God”. Robert then blessed his leg and bade him stand. The two hermits returned to Knaresborough, and continued to live together until Robert’s death, when Ive received his last benediction and became his successor.

About Robert and King John [Excerpted from page 153]:

Robert of Knaresborough boldly spoke his mind to King John. When the kind and his retinue arrived at the hermitage, Robert was prostrate before the altar, and would not leave his devotions, although aware of their presence. At length Sir Brain de Lisle roused him, saying : “Brother Robert, rise quickly : Lo! the king is here who would speak with thee”. The hermit arose, and having picked up from the ground an ear of corn, held it towards King John, and said : “If thou be king, do thou create such a think as this”: and when the king could make no reply, he added : “There is no King but one, that is God”. Certain of the bystanders regarded the hermit’s conduct as madness, but one replied that Robert was indeed wiser than they, since he was the servant of God in whom all is wisdom. Even the unbelieving despot was duly, if momentarily, impressed by the good man’s boldness. Before Robert, says the rhyming chronicler, tyrants trembled, beasts and birds bowed, and fiends fled.

And according to page 134: The genial, generous Robert of Knaresborough was ever surrounded by a crowd of poor pensioners and pilgrims, for which he built a guest-house near his cell:—

Heghe and lawe vnto hym hyed

In faith for to be edified.

—

1. Lanercost Chr. (Bannatyne Club, 1839), 25-7 ; Metrical Life (Roxburghe Club) ; N. Roscarrock’s Life, Camb. Univ. MS. C.Add. 3041, 377-9b.

2. R. Stodley, Vita, B.M. Harl., 3775 f. 76 ; “ubi quondam uilla grandis que Rothferlington vocacatur”. Rudfarlington, once a large township, is now a farm. A field towards Crimple Beck is called Chapel Garth.

3. 8 kal. Octobris, 1218, Chr. Lanercost, 25. The Dict. Nat. Biog. gives c. 1235, but Chart. R. 1227 grants land of Brother Robert “formerly hermit there” to Ive.

4. The metrical Life affirms that Ive gave the place to Coverham Abbey by charter.

5. Chr. Maj. (Rolls, 57) III. 521 ; iv. 378 ; 195.

6. Dodsworth, Church Notes. (Rec. S., 34), 158. The glass is said to have been removed during the last century (? into Lincolnshire).

Eeew!

Okay. This is too good. I’m transcribing along in Shrines of British Saints …la la la…and I come across this passage:

“There was also a prevailing idea that a healing oil exuded from the tombs of certain saints as those of St. Andrew, St. Katherine, and St. Robert, the founder of the Robertines at Knaresborough, which are said to have sweated a medicinal oil.”

First, I have to share my giggle that on first reading I read it was the monks that sweated the oil. Yuk. I had to re-read the passage, and….der…oh yeah, that would be the tomb that was sweaty. (Still gross, however.)

We won’t go into how ridiculous a sweaty tomb seems. Didn’t they do something like that for a comic moment in the film The Mummy? When the sarcophagus pops open and two of the characters declare the mummy inside as “juicy.”

But all the silliness and sweatiness aside, here is this amazing nugget tucked into my book. Robertine monks?? I already know that holy tombs can sweat holy oils (again, eew), but I have never heard of Robertine monks! And I don’t really care how sweaty they are, this bears further investigation. I will be sure to post more info as I dig.

Ah…I just love it when you get a bonus with your book!

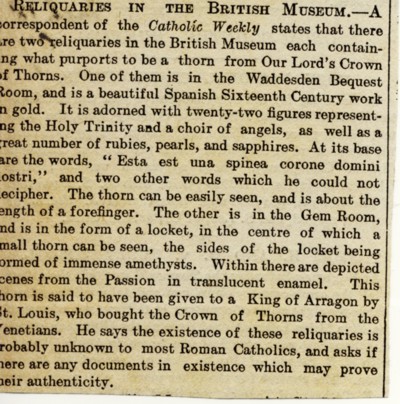

Tucked inside my copy of Shrines of British Saints was this lovely little clipping. Not sure what paper published this little clip, but the clipper made note of the date: March 18, 1907.

Transcription:

Reliquaries in the British Museum.—A correspondent of the Catholic Weekly states that there are two reliquaries in the British Museum each containing what purports to be a thorn from Our Lord’s Crown of Thorns. One of them is in the Waddesden Bequest Room, and is a beautiful Spanish Sixteenth Century work in gold. It is adorned with twenty-two figures representing the Holy Trinity and a choir of angels, as well as a great number of rubies, pearls, and sapphires. At its base are the words, “ Esta est una spinea corone domini nostri ,” and two other words which he could not decipher. The thorn can be easily seen, and is about the length of a forefinger. The other is in the Gem Room, and is in the form of a locket, in the centre of which a small thorn can be seen, the sides of the locket being formed of immense amethysts. Within there are depicted scenes from the Passion in translucent enamel. This thorn is said to have been given to a King of Arragon by St. Louis, who brought the Crown of Thorns from the Venetians. He says the existence of these reliquaries is probably unknown to most Roman Catholics, and asks if there are any documents in existence which may prove their authenticity.

Btw, belated congratulations to the Haddington Harriers who won the Irish Cross Country title near Elm Park, in Dublin, for the third year running! Race winners were D. Downing, of Haddington, first place, J. Smith, of Donore, second place, and S. Lee, of Ulsterville, third place.