Robert of Knaresborough

Ask, and ye shall receive.

Curious about those sweaty monks from my previous blog?

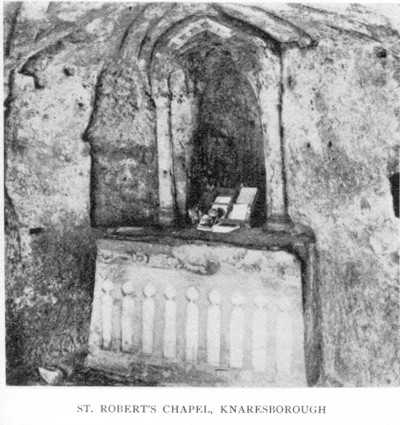

In a nutshell, St. Robert was a hermit and should probably be the patron saint of prisoners as that was a favorite ministry for him, taking in and redeeming, aiding, helping thieves and other prisoners. He seems to have fashioned a small monastic type hermitage in Knaresborough that included a cave dwelling, a chapel, a guest house, and a farm.

As to the group of monks called “Robertines,” I haven’t learned too much more about that. My guess is this Robert was a charismatic leader and holy man and of the “crowds” that came, a few chose to stay and follow him. Who these “Robertines” were I’m not sure, but probably officially consisted primarily of Brother Ive, who was Robert’s hermit companion. The “Robertines” became Trinitarians, as it was that group that took over the hermitage and chapel after Robert’s death.

Certainly the demise of Robert was treated like the demise of an Abbot, with the property reverting to the King (and benefactor) until a successor could be named.

Here’s the story of Robert of Knaresborough, excepted from Mary Rotha Clay’s The Hermits and Anchorites of England.

The story of Robert of Knarlesborough [Excepted pages 40-44]:

Robert of Knarlesborough was a citizen of York. According to a fourteenth-century chronicle, his surname was Koke. Leland calls him “one Robert Flowr, sunne to one Robert Flowr, that had beene 2 tymes Mair of York”. Other authorities give his father’s name as Touke or Tok Flour, and his mother’s as Onnuryte, Simunina, or Sunniva.1 The pious youth became a lay brother of Newminster in Northumberland, but after a few months he sought stricter seclusion. Being doubtless well acquainted with Knaresborough (only eighteen miles from his home), he determined to join a certain knight, rich and famous, who, having fled from the lion-like wrath of Richard I, was living apart from men on the banks of the Nidd. The two men dwelt together in a cave ; but, after the king’s death, the fugitive warrior returned to the world :—Langir lyked hym noght that lyffe

Bott als a wreche wentt to hys wyffe,

leaving the “soldier of Christ” alone.

The young solitary was befriended by a virtuous matron named Helena, who gave him the chapel of St. Hilda at Rudfarlington in Knaresborough forest.2 There he abode for a while, but when thieves broke into his hermitage, he moved on to Spofforth. Then, fearing lest the crowds which followed him should move him to vainglory, he accepted the invitation of the monks of Holy Trinity, York, to join some of their number at Hedley. The young zealot, clad in an old white garment, who would eat nought but barley bread and vegetable broth, was not a comfortable companion, and Robert, regarding his fellows as “fals and fekyll,” returned to St. Hilda’s. The noble dame was passing glad to see him, and provided a barn and other buildings for his use. William de Stuteville, Constable of Knaresborough, passing by, saw the dwelling, and when he heard that one Robert, a devoted servant of God, lived there, he cried : “This is a hypocrite and a companion of thieves!” and bade his men “dyng doune hys byggynges”. The homeless hermit took his book and fared through the forest to Knaresborough :—To a chapel of syntt Gyle

Byfor whare he had wouned a whyll

That bygged was in tha buskes with in

A lytell holett : he hyed hym in.

But again the lord of Knaresborough went a-hunting, and when he was smoke rising from the hut, he swore that he would turn out the tenant. That night there “appered thre men blacker than Ynd,” who roused him [William] from his restless sleep. Two of them harrowed his sides with burning pikes, whilst the third, of huge stature, brandished two iron maces at his bedside : “Take one of these weapons and defend thy neck, for the wrongs with which thou spitest the man of God”. William cried for mercy and promised to amend his deeds, whereupon the vision vanished. Early in the morning the terrified tyrant hastened to the cell, and humbly sought pardon :—Roberd forgaff and William kissed

And blythely with hys hand hym blyssed.

The penitent baron then bestowed upon Robert all the land between the rock and Grimbald Kyrkstane, besides horses and cattle.

William de Stuteville was succeeded by Brian de Lisle, who regarded the hermit as his faithful friend. It was he who besought King John to visit Robert (see p. 153). This visit resulted in the further endowment of the cell. John bade Robert ask what he willed, but he relied that he had enough, and needed no earthy thing. When Ive found that alms for the poor hand not been asked, he persuaded his master to follow the king, from whom he receive the grant of a carucate of land. This land was appropriated to the use of the poor, and Robert refused to pay tithe for it to the rector, to whom he indignantly granted “crysts cursynge” for his covetousness.

Robert was “to pore men profytable”. He gathered alms for the needy, fed them at his door, and sheltered them in his cave. The complaint made by the angry baron that the hermit was a receiver of thieves had some truth in it. In the rhyming life, Robert speaks of the corn required for “my cayteyffes in my cave”. His favourite form of charity was to redeem men from prison :—To begge an brynge pore men of baile

This was hys purose principale

St. Robert died on the 24, September, 1218.3 He had been a benefactor to many, and great was the grief of the mourners. As he had foretold on his death-bed, the monks of Fountains sought to bear away his body, but Ive carried out his master’s wish to be buried in the chapel of the Holy Cross, where he had himself prepared a rock-hewn grave.I wyll be doluen whar so I deghe

Beried my body thare sall ytt be

Wyth outen end here wyll I rest

Here my wounyng chese I fyrste

Here wyll I leynd here wyll I ly

In this place perpetuely.

The chroniclers call St. Robert’s first hermitage “the chapel of St. Giles,” describing it as a dwelling under the rock formed by winding branches over stakes in front of a cave. They relate how his brother Walter, who was mayor of York, thought this cavern and wattled hut no fitting habitation for him, and suggested that he should join some community. Robert replied : “This is my resting-place for ever : here will I dwell, for I have chosen it”—an answer which recalls the antiphon sung when a recluse was about to enter his life-long retreat. Walter therefore sent workmen from the city who laid the foundations of a chapel in honour of the Holy Cross, built of hewn stone. Evidently this chapel adjoined the cave, and replaced the humble oratory of St. Giles. […]

After Robert’s death, the cell was claimed as Crown property. A writ was issued (1219) to the Constable of Knaresborough to cause “our hermitage” to be given into the custody of Master Alexander de Dorset. The original grant was afterwards confirmed to Brother Ive, hermit of Holy Cross (1227).4 The chapel became a place of pilgrimage, and many miracles of healing were wrought there, especially about twenty years after the saint’s death. “The same year (1238) shone forth the fame of St. Robert the hermit at Knaresborough, from whose tomb medicinal oil was brought forth abundantly.” Matthew Paris, naming in 1250 the chief personages of the last half-century, mentions in particular St. Edmund of Pontigny, St. Robert of Knaresborough, and St. Elizabeth of Hungary.5 The new priory (or “House of St. Robert”) was granted to the Trinitarian Friars, and it was fitting that the “Order of the Holy Trinity for the Redemption of Captives” should become successors of the saint two had delighted in releasing men from prison. The name Holy Cross or Holy Rood was superseded by that of the hermit. In 1257 Richard, Earl of Cornwall, confirmed to the Order the chapel of St. Robert.

About Robert the Farmer [Excerpted from page 101]:

Robert of Knaresborough was another hermit-husbandman. He fared frugally, but one day he was left hungry, for robbers invaded his dwelling and stole his bread and cheese. After a time he was granted as much land as he could dig, and later, as much as he could till with one plough. he was also given two horses, two oxen, and two cows. Robert’s parable was an ear of corn (p. 153) ; and the miracles ascribed to him are the miracles of a farmer. He tames the wild cow, and yokes to his plough the stags which trample his corn :—Hertes full heghe of hede and horn

Vsed to come to Robertt corn. . .

He wentt and wagged att them a wand

And draffe thise dere hame wt hys hand.

This legend, and also that of a counterfeit cripple, who begged a cow from St. Robert, were depicted in a window set up in Knaresborough church in 1473.6

About Robert and Brother Ive [Excepted from page 129]:

Robert of Knaresborough was joined by Ive and by several servants, who shared his labours. The story of Ive seems to show that even in the “solitary” life, two were better than one, for the strong would lift up his fellow. One day Ive attempted to return to the world which he had renounced. In passing through the forest, however, he broke his leg with the bough of a tree, and fell into a ditch, where he sat “alas! alas! waloway!” Robert, supernaturally aware of what had happened, hastened thither, and not without mirth at his friend’s plight, pointed the moral : “No man, having put his hand to the plough and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God”. Robert then blessed his leg and bade him stand. The two hermits returned to Knaresborough, and continued to live together until Robert’s death, when Ive received his last benediction and became his successor.

About Robert and King John [Excerpted from page 153]:

Robert of Knaresborough boldly spoke his mind to King John. When the kind and his retinue arrived at the hermitage, Robert was prostrate before the altar, and would not leave his devotions, although aware of their presence. At length Sir Brain de Lisle roused him, saying : “Brother Robert, rise quickly : Lo! the king is here who would speak with thee”. The hermit arose, and having picked up from the ground an ear of corn, held it towards King John, and said : “If thou be king, do thou create such a think as this”: and when the king could make no reply, he added : “There is no King but one, that is God”. Certain of the bystanders regarded the hermit’s conduct as madness, but one replied that Robert was indeed wiser than they, since he was the servant of God in whom all is wisdom. Even the unbelieving despot was duly, if momentarily, impressed by the good man’s boldness. Before Robert, says the rhyming chronicler, tyrants trembled, beasts and birds bowed, and fiends fled.

And according to page 134: The genial, generous Robert of Knaresborough was ever surrounded by a crowd of poor pensioners and pilgrims, for which he built a guest-house near his cell:—Heghe and lawe vnto hym hyed

In faith for to be edified.

—

1. Lanercost Chr. (Bannatyne Club, 1839), 25-7 ; Metrical Life (Roxburghe Club) ; N. Roscarrock’s Life, Camb. Univ. MS. C.Add. 3041, 377-9b.

2. R. Stodley, Vita, B.M. Harl., 3775 f. 76 ; “ubi quondam uilla grandis que Rothferlington vocacatur”. Rudfarlington, once a large township, is now a farm. A field towards Crimple Beck is called Chapel Garth.

3. 8 kal. Octobris, 1218, Chr. Lanercost, 25. The Dict. Nat. Biog. gives c. 1235, but Chart. R. 1227 grants land of Brother Robert “formerly hermit there” to Ive.

4. The metrical Life affirms that Ive gave the place to Coverham Abbey by charter.

5. Chr. Maj. (Rolls, 57) III. 521 ; iv. 378 ; 195.

6. Dodsworth, Church Notes. (Rec. S., 34), 158. The glass is said to have been removed during the last century (? into Lincolnshire).